By Koen Van Impe February 11, 2026

MISP architecture

Getting your MISP architecture right from the start makes all the difference. A well-designed deployment keeps your threat intelligence platform running smoothly, protects your data, and ensures your analysts have what they need when they need it. Poor choices lead to performance bottlenecks, security gaps, and maintenance headaches that only get worse as your data grows.

Understanding MISP’s architectural foundations

MISP is not a single monolithic service. At its core, it is a web application handling user interactions and API requests, backed by a database storing events and attributes. Alongside that, an in-memory database supports sessions, job queues and caching, whilst Python scripts power enrichment and external integrations.

This modular design gives you flexibility, but each component has its own requirements. The database needs fast storage and tuning. The web tier needs to cope with traffic spikes when feeds update or analysts run large queries. Background workers need enough headroom to keep up with correlation and enrichment jobs. Understanding how these parts fit together helps you make sensible decisions about performance, redundancy, and scaling.

Your architecture should also reflect how intelligence flows through your organisation. Some deployments are central hubs receiving data from dozens of external communities, whilst others are internal knowledge bases fed by curated sources. The volume, frequency, and sensitivity of your intelligence will influence decisions around storage, network segmentation, and access controls.

Core components and architectural influence

MISP runs on a modular LAMP stack. How the components work together determines how well your deployment scales and performs.

| Component | Role | Architectural influence |

|---|---|---|

| Linux / Apache | Serves the web interface and handles REST API requests. | High-traffic environments benefit from load balancing across multiple nodes. |

| MariaDB / MySQL | Stores events and attributes in a relational database. | Fast storage is essential. I/O latency is one of the quickest ways to ruin performance. |

| PHP | Runs the core application logic and scripts. | Default memory limits and execution times rarely hold up at scale. |

| Redis | Manages caching and background job queues. | |

| Python | Powers MISP modules and custom integrations. |

Deployment architecture options

Where you host MISP is a strategic decision. It touches data sovereignty, regulatory compliance, and trust. Most organisations land on one of three models:

-

On-premises: Full control over hardware, physical access, and data protection. Often the only sensible choice where you handle classified intelligence or operate under strict data residency requirements. Air-gapped deployments are possible when you need absolute isolation. The trade-off is that you own everything from hardware failures to capacity planning.

-

Cloud-native: AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud provide convenience and scalability. For some teams this is a great fit, but it is not universally suitable. You are still placing intelligence on someone else’s infrastructure. For sensitive intelligence shared under strict handling restrictions, that can be a blocker regardless of the technical safeguards.

-

Hybrid: A practical compromise. Keep sensitive intelligence on-premises whilst using cloud infrastructure for less critical workloads. A common pattern is an internal instance in your own environment with a cloud-hosted edge node for external communities. Hybrid can work well, but it does add operational complexity.

Where your data physically resides matters. Some cloud providers operate under legal jurisdictions that could compel access to data. For critical infrastructure, government agencies, and teams handling sensitive intelligence, this can create unacceptable risk. Even within allied nations, differences in legal frameworks can be enough to change your hosting decision.

Equally important are the intelligence sharing agreements. Many feeds come with explicit handling restrictions, such as Traffic Light Protocol (TLP) classifications, community-specific rules, or constraints on storage outside certain jurisdictions. Before you commit to any cloud deployment, review your sources and their distribution requirements.

Installation strategies

How you install MISP affects day-to-day maintenance and how quickly you can roll out updates. There are two common approaches, plus clustering options if you have more demanding requirements.

Native Linux installation

This is the traditional route: install the complete stack directly onto a Linux server. Ubuntu remains the primary development platform. Installation usually means pulling the latest code from GitHub and working through dependencies. If you are comfortable with Linux system administration, it is straightforward, but you do need a working understanding of how the stack fits together.

Red Hat-based systems are in a better place than they used to be, with reliable pre-built RPM packages now available. The catch is timing. When there is a new MISP version, you may have to wait for the RPM update. For many organisations that delay is acceptable. If you need fixes quickly, or you want to control the upgrade schedule, building from source keeps you in charge.

Containerised deployment with Docker

Running MISP in Docker containers gives you portability and consistency. Images bundle the application code, dependencies, and the correct system library versions. You can pull pre-built images for straightforward deployments, or build images in-house if your policies or customisation needs require it. The in-house route needs Docker expertise and an ongoing patching process.

Running containers directly in cloud services without proper orchestration can look attractive, but it is often harder than it sounds. Configuration and troubleshooting become more painful when the container platform adds another layer of abstraction. In many environments, running Docker on a Linux host (on-premises or a cloud VM) gives you better control and fewer surprises.

Clustering and high availability

Kubernetes and other orchestration platforms can run MISP in a clustered way, managing scaling and failover. This can make sense if you run MISP as a service for multiple teams, each needing isolated instances. For many organisations, though, the extra complexity is not worth it unless you truly need that level of scale.

Node architecture and data flow

One of the most important architectural choices is how many MISP instances you run and how they connect. This is not just about availability. It is about controlling what reaches your security controls.

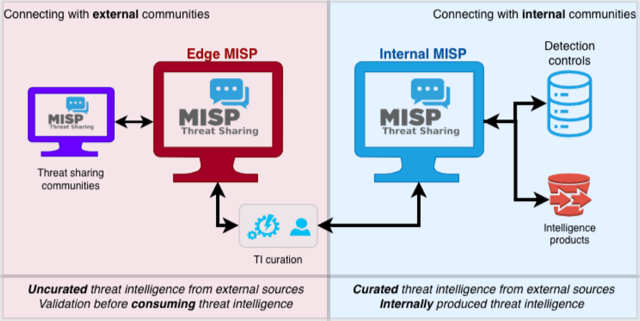

Edge and Internal nodes

Running separate Edge and Internal nodes sounds like extra work, but it solves a critical problem. You do not want raw, uncurated intelligence from external sources flowing straight into your SIEM, firewall, or EDR.

The Edge node sits at the perimeter. It connects to external communities (ISACs, regulatory bodies, commercial threat feeds, CSIRTs) and ingests what they send. This is where you validate, normalise, and curate the data. Think of it as quality control. You can remove obvious false positives, enrich indicators, and decide what is actually worth passing on.

The Internal node only receives curated intelligence from the Edge. This is what should connect to your security controls and what your analysts should rely on day-to-day. External intelligence is useful, but it is not tuned to your environment. If you push everything straight into blocking and detection, you are effectively outsourcing your security posture.

In practice, the cleanest way to run this split is to treat the Edge as an intake queue. Keep external sync broad, but keep distribution conservative. Apply tags and basic validation on the Edge, then only sync or export what you have reviewed and are prepared to operationalise. That review step can be as lightweight or as formal as you need, but it should exist.

Data volume and correlation

High-volume feeds can overwhelm MISP if you are not careful. Correlation is powerful, but it is resource-intensive. When you ingest millions of indicators, you need to make pragmatic choices about what you store, what you correlate, how long you keep it, and what you treat as a lookup-only source.

A useful model is to separate intelligence you want to drive detections and blocking from intelligence you want to keep for analyst search and context. If you blend those together, your internal systems will either get flooded with noise or you will end up turning off integrations entirely. Decide early which sources are allowed to become operational indicators, and be comfortable keeping the rest as reference.

Integration placement

Your MISP instance needs to push intelligence to security controls. Where you run these integrations matters. Some rely on Python scripts that need network access to both MISP and the target system. Others write indicators to files that downstream systems collect.

For most deployments, running integrations on the MISP host keeps things simple. You avoid extra servers, extra network paths, and extra authentication plumbing. Only move integrations elsewhere if you have a clear reason to do so.

Network connectivity

If your Edge node connects to external communities, check access requirements early. Some providers allow connections from anywhere, others restrict access to specific IP ranges. This becomes particularly important if you are planning high availability across regions or providers.

Resilience and availability

Eventually, something will fail. Hardware breaks, networks drop, mistakes happen. The question is how quickly you can recover.

Active-passive failover

For most organisations, active-passive strikes the right balance between complexity and resilience. Run your primary instance(s) (both Edge and Internal) as active, and keep standby hosts ready with database replication. If the primary fails, promote the standby and restore service with minimal data loss.

Database replication

Your database holds everything: events, attributes, user data, and configuration. Replication keeps a live copy on the standby host. Set it up carefully and test failover regularly. Replication is mature and reliable, but only if you have proved it works before you need it.

File storage

The database is not the whole story. MISP stores attachments, samples, and logs on disk. Plan how that data moves with your failover. Common approaches are shared storage that both nodes can access, or file synchronisation between nodes. Both work, and both have trade-offs.

Backups

Failover is not a backup. It protects you from hardware failure, not from corruption, accidental deletion, or security incidents. Take regular backups of the database, configuration, and attachments. Store them somewhere separate, and restore-test them periodically.

Monitoring

Monitor reachability and core services (web, database, Redis). Also monitor worker health and queue depth. A system can look fine from the outside whilst jobs quietly pile up.

Quick decision guide

Deployment model

- Classified intelligence, strict residency, or restricted sharing agreements: choose on-premises first

- Mixed sensitivity: hybrid is often the least painful compromise

- Cloud-native: only if your intelligence handling rules allow it

Installation approach

- Want maximum control and easiest troubleshooting: native installation on Ubuntu

- Need repeatable environments or multiple instances: Docker, preferably on a Linux host

- On Red Hat and happy with packaged releases: use RPMs, accept possible lag behind releases

Node layout

- Connecting to external communities: use Edge and Internal separation

- Small, internal-only use: one node is often enough

Availability

- Most teams: active-passive with tested replication, backups, and a runbook

- Complex platforms: only consider orchestration if you have the skills and a clear need